I read carefully the recent Bill Gates memo, “Three Tough Truths about Climate Change” (28 Oct 2025), which caused a lot of commotion on social media. It was worth a close read, and I am still thinking about it, as well as tracking the media reactions, which have often been, in my view, exaggerated. Certain voices want to make it sound as though Gates has become a climate-change denier, which is quite far from the truth. (For relatively balanced coverage, see, for example, New York Times, Time Magazine, and Le Monde.)

In some ways, what Gates is saying is both more reasoned and more strategically provocative than the social media reactions would suggest. As one of the world’s most generous philanthropists, his thoughts deserve to be taken seriously, not dismissed out of hand with the reflexive irony, outrage, and invective that has so deeply infected the modern Internet. (I wrote about this in a previous post.)

In other ways, however, this “Gates Note” is a new version of an old argument that has distracted the global development community for decades. Is there more economic value to be had from investing in emissions reduction, or in people? Framing the question in this binary way — which leaves out the rest of life on this planet, while ignoring the complexity of the climate system and its tipping points — does not help us advance towards true global solutions to enormously complicated and intertwined problems.

But that is a huge topic, and not what I aim to address specifically in this article. I want to call attention to how the Gates memo is written, and argue for a rewrite.

Gates, or his writing team, uses a few stylistic methods that can be subtly misleading to the reader, especially readers who are not very familiar with the climate change literature. Here are two prominent examples from the article to illustrate my point.

Example 1. “Global warming will probably be less than 3 degrees C by 2100”

This headline appears over a graph showing different global temperature scenarios published by Climate Action Tracker. Why do I characterise Gates’ headline as misleading? Because he uses words that tone down the meaning — and therefore the impact on the reader — of a very alarming projection.

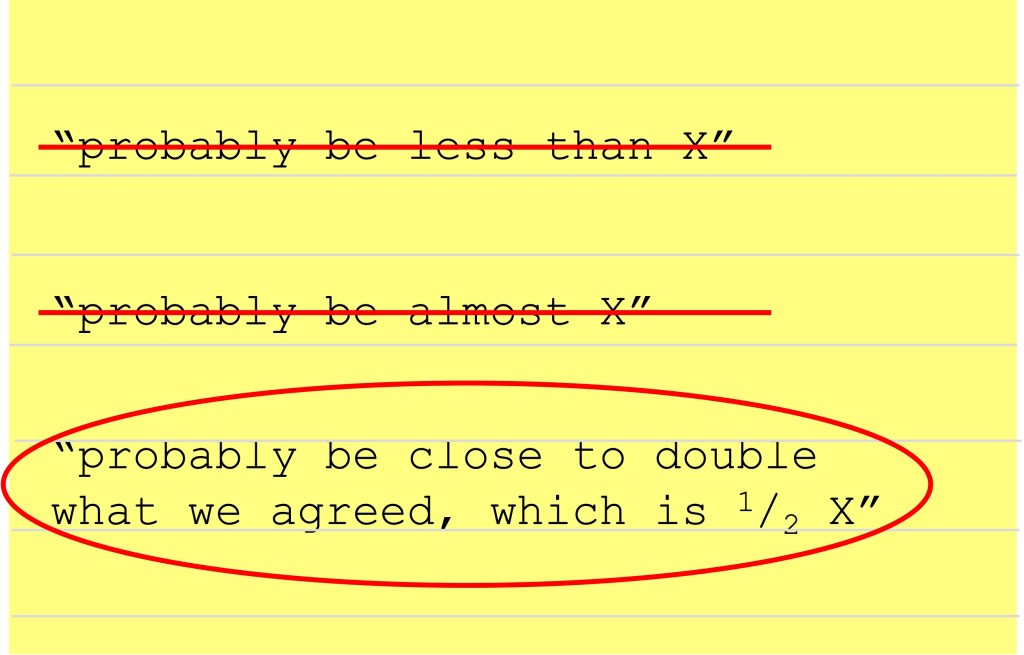

Rhetorical techniques are best understood by looking at counterexamples. Here is another way to write that same headline: “Global warming will probably be almost 3 degrees C by 2100”. Note the emotional impact of that word “almost”, compared to the Gates Notes version. “Probably be less than 3 degrees” says, “don’t worry.” The reader likely feels a bit calmer about climate change after reading it. “Almost 3 degrees”, on the other hand, triggers a different response in most readers: “Oh, that doesn’t sound good, they must be saying that it’s approaching a very risky level.” Which is correct.

Here is still another way to write the headline, conveying exactly the same information but with yet another stylistic choice: “By 2100, global warming will probably be close to twice the 1.5 degree limit agreed to in Paris in 2015.” Remember that the headline in the Gates Note is pointing to the upper range estimate of the current policies scenario in the respected Climate Tracker model. That model indicates a range of 2.5-2.9 degrees warming if there are no further policy changes, and assumes full implementation of those policies now in place. (In the real world, neither of those two assumptions seems likely to me, but that is how modelling works.)

Underscoring the need for underscoring

The second alternative headline I presented above is considerably more alarming than the Gates version. And yet, it is also the version that is most in line with the sense of alarm and urgency that is consistently reported by a broad consensus of the global scientific community studying climate change. The UN Secretary-General has been characterising that consensus, and the sense of urgency with which it is conveyed, as “code red for humanity” since 2021. In other words, this scenario should be seen as alarming. It does no service to anyone, especially those in poverty, to tone down the weight of this projection by using this subtle-but-powerful stylistic writing choice, “probably less than”. The impact of such a stylistic choice may seem like a nit-picky editorial detail, but this headline is prominent, and it is characteristic of the whole article’s tone and message. Such details are especially important when the writer in question is one of the world’s richest and most famous people, whose voice carries great influence, especially in the global development community, where the Gates Foundation is one of the world’s biggest players. (Annual development aid funding by the Gates Foundation exceeds that of Sweden, for example, by a significant margin.)

Raising Earth’s surface temperature by somewhere between 2.5 and 2.9 degrees by 2100 does not sound like a large change — unless one is well-versed in what these numbers mean in terms of real-world impacts. So the urgency of the situation needs to be underscored, repeatedly, for audiences new and old. A temperature rise that high would most likely result in at least a half-meter of sea-level rise as well, which translates to hundreds of millions of people having to leave their coastal homes, and a slow-motion (from a human perspective) climate-related string of other catastrophes for both people and nature, unfolding over decades. A phrase like “probably less than 3 degrees”, which is calculated to emphasize the “doesn’t sound so bad” emotional effect on the reader, and to downplay, or even direct attention away from, the scientific consensus regarding the grave risks involved, is therefore misleading in its tone, whether or not that was the writer’s conscious intention.

Example 2. “Innovation has cut future emissions by 40% in just 10 years”

This headline, which appears over a graph showing IEA emissions projections from both 2014 and 2024, sounds very hopeful. It is true in some sense, but it could also be characterised as misleading, as I explain below. If Example 1 demonstrates how to tone down an alarming projection, this choice of language in Example 2 demonstrates how to exaggerate the meaning, and therefore the positive rhetorical and emotional impact, of a very modest piece of trend-forecasting.

To be very clear, “future emissions” do not actually exist. So innovation cannot “cut” them. “Future emissions” are a projection, an educated guess based on trends. The word “cut” implies that something has made a physical impact in the world, that a real action has been taken; but no real emissions have been reduced. What has been reduced is the number attached to our best formal guess about where emission levels might be in 15-20 years. The reduction in that estimate is good news, but it is not a cut.

This is a subtle point, but it is important to see it if one wants to read past the rhetoric and engage with the intellectual argument that Gates is making. This headline makes it sound as though “innovation” is a kind of actor in the drama, a powerful force for emissions reduction, one that we can count on to keep cutting away at emissions, almost by itself. The headline, as well as Gates’ long list of bulleted examples, comes close to presenting “innovation” as a kind of benevolent “invisible hand”.

I do not want to sound overly negative myself: a lot of innovation and change has been happening, some of it faster than expected, especially in energy and transport. I celebrate our advances just as much as Gates does. But as Gates says elsewhere in the piece (at least twice), innovation requires that the world has “the right investments and policies in place.” In other words, we cannot count on innovation unless the world’s governments, large-scale investors, and other policy-makers keep building and expanding the right envelope of prioritised incentives, capital, and regulation that makes innovation possible at the scale it needs to happen. And the lack of such prioritisation is precisely the thing that underlies the sense of urgency and alarm among most climate researchers, UN analysts, and interested observers like myself.

A better choice might be something like this: “Estimates of future emissions have been reduced by 40% during the past 10 years.” I know, this headline is much less exciting. But it is more accurate. It has the additional benefit of not making it sound like we reached into the future with our emission-cutting scissors and somehow made a cut. The story is positive enough as it is: again, with the right incentives and investments, we can make significant progress in reducing the sources of our emissions. And we have.

Conclusion: Some (unasked-for) editoral advice

I have not attempted to review or critique the complete Gates Note, which addresses many complex issues that I often scratch my head about, but also says many things that I fundamentally agree with. Let me state clearly that I deeply admire what Bill Gates is doing, and promising to do, in our world. It is worth remembering that he is under no obligation to give his money away. I sincerely wish more of the world’s ultra-rich would follow his example of redirecting acquired wealth towards solving global problems. And for all I know, Gates might be right in his calls for investing more in human welfare as a strategy for addressing the climate crisis. I have heard powerful arguments in favour of a similar approach from other very knowledgeable people whom I have met personally, including heads of central banks in the countries most affected by climate-related damages. I myself have long argued that we are not paying enough attention, and not paying enough money, for the climate adaptation actions that the world requires; and much of what Gates recommends that we do contributes, in ways both direct and indirect, to that very large category of “climate adaptation”, as he notes himself.

But this Gates Note, “Three Tough Truths about Climate Change“, is ultimately not convincing to me, overall, partly because of these subtle stylistic choices that tend to understate and oversimplify the current scientific consensus, and partly because one of Gates’ central arguments — that innovation will take care of many problems, as long as the right investments and policies are in place — bends back on itself logically. The “right” investments and policies are not in place, at least not in all the places they need to be and not at the scale we need for transformation in our economies.

I also wish that Gates had not presented his three main opinions, which are certainly valid points of discussion, as truths. They may be true for him, but they are not true for me and many other people. The phrase “three propositions” would have been a good alternative to “three truths”, and would have done a better job of inviting people into genuine discussion and debate on these very important questions. Declaring opinions to be unarguable truths tends to feed the monster of social media opprobrium.

I conclude with some unasked-for general editorial suggestions to Mr. Gates (these are more like wishes, since they are very unlikely to happen). Reconvene your consulting and writing team. Tell them to tone down the polemics around “pivoting”, and ramp up the whole-systems thinking. Bring in some different voices to advise you on what investments will make the most impact, from a balanced-portfolio perspective (how about Nick Stern and Partha Dasgupta?). If you still feel that what you want to invest in is people, I support your choice 100%. It’s your money, and investing in the needs of people is a wonderful and deeply necessary thing to do.

But please, don’t use the arguments you have presented (at least, in the way you have presented them) in an effort to reduce the political will to invest in climate mitigation and adaptation, directly, in favour of more investments in human well-being. Right now, we need a both/and approach: more of everything, in both departments, and preferably in ways that are linked up in smart, systemic ways.

Please, Mr. Gates, do a rewrite.